To observe the five-year anniversary of the burning of the Third Precinct at the beginning of the George Floyd Revolt, we have prepared a timeline tracing the trajectory of anarchist contributions to uprisings against the police from the Rodney King riots of 1992 to the uprising in Minneapolis in 2020. This story has never been told in full; we hope this cursory effort will help participants in tomorrow’s movements to understand the history that they are part of.

Needless to say, this is just one of many ways to tell this story. Countless historical threads converged in the George Floyd uprising. We could trace some of them back to the hip hop underground, others to gang truce mediation efforts, others to the Black Panthers. But this is one of them.

Demonstrators in May 2020.

Today, five years after the uprising of 2020, it is easy to forget all the victories that the movement against police and white supremacy has won since the turn of the century. Two decades ago, it was difficult to see how to expand the conversation about police violence; no one could have imagined that in 2021, even after a bipartisan campaign against the proposal, 44% of voters in a major metropolitan area would vote to abolish the police. Two decades ago, it was unthinkable that tens of thousands of people would embrace direct action and take up black bloc tactics. If we have lost some of this ground thanks to the reactionary administration of Joe Biden and the fascist government of Donald Trump, this does not mean that the struggles of the past two decades were for naught. It should only serve to remind us that in a pitched conflict, we cannot rest on our laurels—we must constantly be fighting to build the world we want to live in.

Until the Ferguson rebellion, very little was known about how many people the police kill in the United States. Police departments and federal agencies did not release the statistics. The only ones who were really speaking about the issue were those whose communities were immediately impacted by police violence and those who had a systematic analysis of the institution of policing. Today, by contrast, news outlets like the New York Times freely publish statistics about police murders.

Why was the fight against racist police murders able to produce the most powerful social upheaval in living memory? The movement that eventually led to the George Floyd uprising got off the ground in the first place because, starting with the protests against the murder of Oscar Grant in 2009, the participants were able to connect the following crucial elements:

- An abolitionist analysis that explained why the murders were occurring more persuasively than any liberal or conservative narrative.

- A set of reproducible tactics that were immediately associated with that analysis, so people could easily take action if they found it convincing.

- Concrete points of intervention—including specific times, places, participants, and targets.

Other movements have not been establish this connection between analysis, action, and context, and have subsequently remained stunted. If we want to mobilize an effective resistance to the aspiring autocrats who hold power today, or to industrially-produced climate change or other threats, we have to learn from the George Floyd uprising.

It was also crucial that the movement against police and white supremacy centered those who have the least cause to preserve the existing order. This should not be lost on middle-class people who hope that others will join them in resisting the Trump regime. In order to involve enough people to succeed, any movement against Trump will have to address the material needs of the oppressed, giving them a stake in the fight. If we don’t want to live under autocracy, there is no way around it—we have to organize against all forms of oppression.

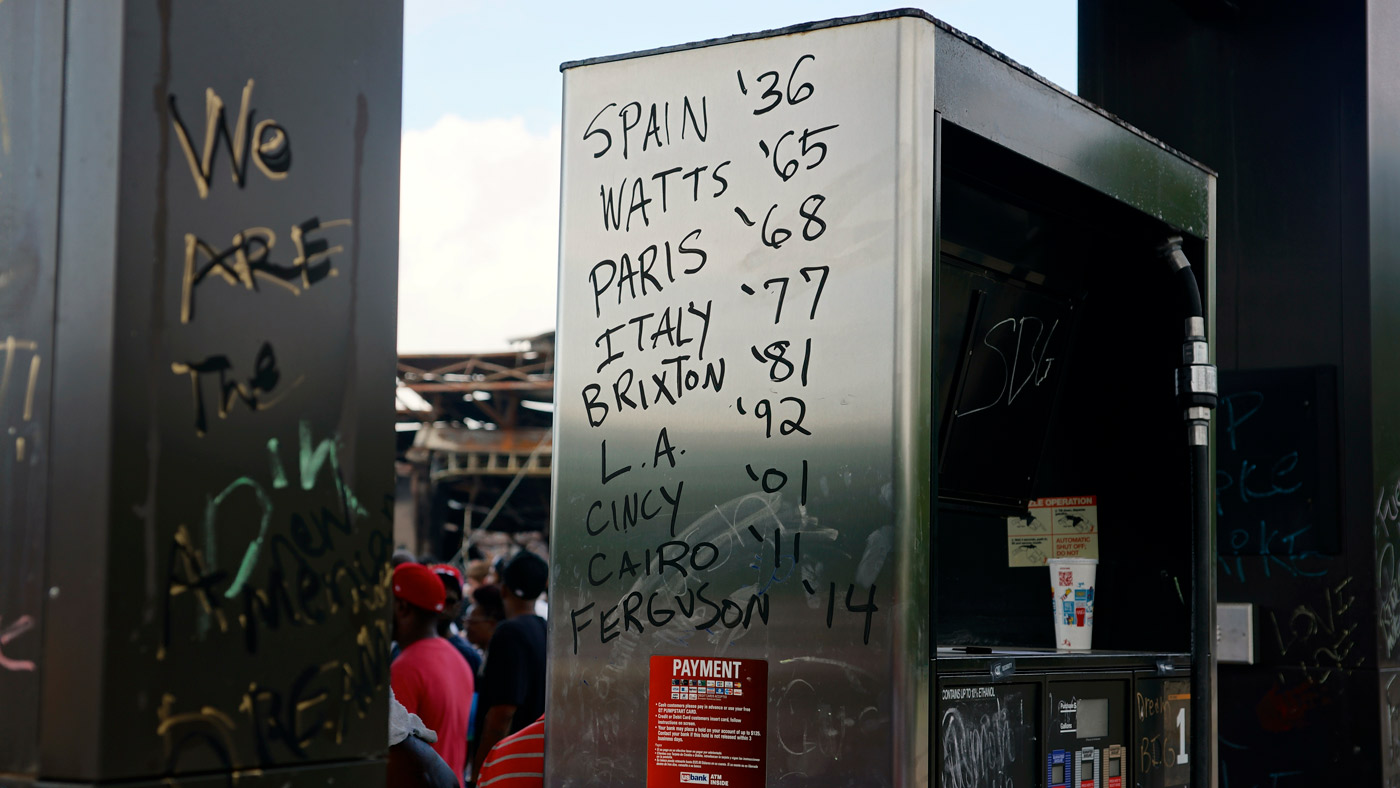

Graffiti on the gas pump at the burnt QT in Ferguson in August 2014, placing it in a context of eight decades of uprisings.

I. Prehistory: From the Los Angeles Riots to the Murder of Oscar Grant

Rioting in response to police murder is as American as apple pie. The previous generation was deeply impacted by the riots in Watts in 1965 and in Detroit in 1967, among others. To trace the trajectory of contemporary anarchist involvement in movements against the police, however, we’ll start in 1991.

LOS ANGELES, March 3, 1991—On the shoulder of the freeway, police are beating a man. Because we are in the US, and because the man is Black, we will know that this is a routine event, an ordinary brutality, part of the very fabric of everyday life for non-whites. But something is exceptional this time. There is an observer, as there often is, but the observer holds in his hands an inhuman witness, a little device for producing images which are accepted as identical with the real. The images—grainy, shaking with the traces of the body behind them—enframe this event, defamiliarize it, make it appear in all its awfulness as both unimaginable singularity and example of a broader category of everyday violence. The recorded beating of Rodney King marks, as many have noted, the beginning of one of the most significant episodes of US history.

Los Angeles, 1992.

April 1992

In Los Angeles in April 1992, a jury acquitted the police officers who had beaten Rodney King, setting off a citywide uprising. In that largely pre-digital era, when news traveled somewhat more slowly, narratives about those events reached many young people through music, including songs by Dr. Dre, Sublime, and other Los Angeles locals.

The riots exerted a formative influence on an entire generation. Satellite actions took place from San Diego and San Francisco to Las Vegas and Atlanta. In 1996, smaller scale rioting took place in St. Petersburg in response to the police murdering an 18-year-old Black man named Tyron Lewis.

Today, when social media has been saturated with footage of police senselessly beating and murdering people—especially Black and Indigenous men—it could seem almost quaint that footage of the beating of Rodney King inspired such uproar. The democratization of video technology has contributed not only to outbreaks of unrest like the LA riots and the George Floyd Revolt but also to desensitizing and accustoming people to racist police violence.

Los Angeles, 1992.

The 1990s

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the do-it-yourself punk underground helped contribute to a renaissance of anarchism around the world. One of the networks that emerged in the United States was Anti-Racist Action, modeled on Europe’s Anti-Fascist Action but adjusted to account for how central racial oppression has always been to capitalism in North America.

The environmental movement also contributed to the reemergence of anarchism. Thanks to Earth First! and the earth and animal liberation movements, a powerful current of direct action organizing spread in ecological circles; it was only later that the shifts heralded by Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth contributed to professionalizing and taming them. At the turn of the century, green anarchist publications like Disorderly Conduct, Anarchy Magazine, and Do or Die helped to introduce insurrectionary anarchism to North America, promoting the idea that anarchists should look for opportunities to fight directly against their oppressors alongside other rebellious elements of the oppressed.

Green anarchists who cut their teeth using militant tactics in forest defense campaigns converged alongside tens of thousands of other demonstrators in Seattle in November 1999 for the protests against the World Trade Organization summit. Some of them participated in the notorious black bloc on November 30 that drew considerable attention to that tactic. This helped to set the template for the next two decades of anarchist street action.

April 2001

In Cincinnati, on April 7, 2001, a white police officer murdered 19-year-old Timothy Thomas. Thomas was the fifteenth Black man Cincinnati police had killed in six years. On April 9, Thomas’s mother joined other protesters at City Hall, where the police chief and the mayor refused to apologize for the murder.

A Cincinnati Police officer pushes his knee into a person’s back in Cincinnati on April 10, 2001.

Angered at these responses, the crowd proceeded to take over City Hall. Windows were smashed, the American flag was removed from the flagpole and turned upside down, and the mayor was forced to leave via the back door. Hundreds more protesters arrived at City Hall that night. As the crowd swelled to 1000, they marched to the central police station.

Anarchists from Cincinnati, some of whom were involved in Anti-Racist Action, participated in the riots that took place over the following days. As the Black anarchist Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin wrote in “Black People Have a Right to Rebel,”

We can soon expect to see other such rebellions in various American cities because similar contradictions exist… The task of Black radicals is not to call for new federal legislation, an FBI investigation, or a citizen review board. We must educate our people about the truth of this system, and begin to build a mass resistance movement against racism and internal colonialism. This resistance should be by any means necessary.

Like the Los Angeles riots, the uprising in Cincinnati was a multiethnic revolt against institutional white supremacy. Yet some of the tensions that were to reemerge in Oakland, Ferguson, and Minneapolis were already evident. As one anarchist collective wrote in July 2001, wrestling with the questions facing non-Black participants,

It’s hard to claim to take leadership from the “Black community” when there’s no one viewpoint predominant in that community. And symbolically “confronting privileged space” is not necessarily the same as supporting the struggle of the Black community.

How essential was anarchist participation in the Cincinnati uprising? By the account of the anarchists who wrote about it, they played only a peripheral role. Nonetheless, the spread of anarchism and the uprising in Cincinnati took place in parallel, as if in response to the same unseen developments. The first half of 2001 was the high point of the movement against capitalist globalization; only five months earlier, in November 2000, one of the only significant mobilizations in the Midwest had taken place in Cincinnati in response to the Transatlantic Business Dialogue conference. After the momentum of the anti-capitalist movement stalled a few months later, anti-police uprisings also paused.

A lone protester in the middle of Race Street throws a can at a police line on April 10, 2001.

From 9/11 to 2007

The attacks of September 11, 2001 interrupted the momentum of social movements in the United States. It took years to fulfill Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin’s prediction that there would be more uprisings.

The authorities had learned from the defeat they had suffered during the WTO meeting in Seattle, when a few hundred police had been outmaneuvered by tens of thousands of protesters. In November 2003, when a few thousand embattled demonstrators gathered in Miami to oppose a summit regarding the proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas, a tremendous force of militarized police was prepared to repress them. Many protesters saw tanks on the streets of the United States for the first time that day—something most people didn’t see until media coverage of the Ferguson uprising in August 2014.

The authorities had copied the strategy of convergence that protesters had used so effectively against global trade summits in Seattle, Washington, DC, Québec City, and Genoa. It was clear that if future uprisings were to take place, they would have to involve more people than could be coordinated through any particular network or mobilization, and they would have to take the authorities by surprise.

The anti-war era (from fall 2001 to summer 2008) was a period of reaction; protest movements were dominated by liberals and authoritarian socialist front groups that sought to limit the range of tactics and strategies that participants could employ. At the same time, as a consequence of the previous cycle of protest against police racism and murder, many local movements against police brutality had been channeled towards demanding civilian review boards and police oversight committees, which rarely had any actual impact on police violence. In some parts of the United States, this was so successful that anarchists perceived local organizing against racist police violence as hopelessly co-opted and reformist.

2008

In 2007, aiming to regain momentum at the end of the Bush era, anarchists around the United States began to prepare for mass mobilizations against the Democratic and Republican National Conventions scheduled for summer 2008. A countrywide network dubbed Unconventional Action took the lead in coordinating, drawing on the convergence model that the anti-capitalist movement had made famous at the turn of the century.

Around this time, anarchists in North America were beginning to encounter the first clumsy translations of The Call, The Coming Insurrection, and the works of Tiqqun, all hailing from the same milieu in France. Many Anglophone readers initially conflated this political tendency with the older brand of insurrectionist anarchism exemplified by Alfredo Bonanno. The French texts drew much of their appeal from association with the anti-police riots that had taken place in the urban peripheries of France in October and November 2005, which struck many readers as more interesting than anything that had recently occurred in the US.

The protests at the party conventions that summer delivered mixed results, but the organizing around them revitalized anarchist networks across the country—for example, giving rise to Bash Back. In the Bay Area, which hosted one of the most vibrant anarchist milieux in the country at that time, the local Unconventional Action group—UA in the Bay—continued to meet after the conventions in order to organize local actions.

At the same time, the global financial crisis of 2008 was setting in. The first significant responses to it took place overseas.

December 2008

On December 6, 2008, police in Greece murdered a 15-year-old anarchist named Alexandros Grigoropoulos. Anarchists all around Greece immediately precipitated a countrywide insurrection, attacking police, destroying business districts, and occupying universities. This ushered in an era of worldwide resistance to austerity measures and police violence. As graffiti in Athens put it, “Sometimes, tear gas can make you see better.”

Demonstrators chase off riot police in Greece in May 2010.

In the Bay Area, anarchists organized a solidarity march that unexpectedly succeeded in pushing past police to enter the Westfield Shopping Mall during the Christmas rush. As participants in UA in the Bay reported afterwards,

We regrouped outside the entrance to the mall. At this point so many curious shoppers had gathered that it was impossible for the police to enter the crowd and arrest anyone else. Several of our comrades were dragged past us by squads of police and into a paddy wagon on the street. Some demonstrators got back on the sound system and began to denounce the police. Unexpectedly, the message resonated with a number of the shoppers, many of whom were people of color who may have had their own beef with the law. Boisterous chants of “Fuck the Police” began to echo off the buildings.

This was a sign of things to come.

December 31, 2008

On New Year’s Eve 2008, a Bay Area Rapid Transit officer murdered Oscar Grant. Like the beating of Rodney King, this atrocity was captured on video; it circulated widely on the internet.

January 7, 2009

On January 7, the day of Oscar Grant’s funeral, an ad hoc group dubbed the Coalition Against Police Execution organized a rally at the Fruitvale BART station where Grant had been killed. The rally drew perhaps a thousand people. The organizers intended to register their disapproval of the police and enable people to let off steam without things getting out of hand, according to the established model. Participants in UA in the Bay have described what happened next:

A member of the crowd would get on the mic and demand action, invigorating the protesters and calling for the crowd to march. Immediately after, the organizers would take back the mic, call for calm, and restate their belief that we should channel our energy into “legitimate” channels. They would promise to march “in ten minutes” or “after this amazing next speaker.” This went on for a number of hours, and the crowd grew restless.

The crowd continued to swell as this continued. A group of anarchists began to gather toward the back of the rally. After a while, it became apparent that the organizers had no intention of marching, while a good many protesters did. So the anarchist bloc, not being ones to wait for permission, began beating improvised drums and left, accompanied by the vast majority of the crowd, including the rally organizers.

That was the crucial moment when, after a period of malaise, anti-police movements in the United States became ungovernable once again. The fact that members of UA in the Bay helped to initiate the night’s events makes it possible to trace a continuous through line from the mass mobilizations of the turn-of-the-century anti-capitalist movement through the cycle of anti-police uprisings that stretched from the Oscar Grant Rebellion to the George Floyd Revolt and beyond.

Everything escalated after we turned toward the police station. Several blocks on, the march met a solitary police car with two officers inside. The crowd quickly approached the surprised officers; being boxed in, they abandoned their car and fled on foot. People started jumping on the hood and roof while others smashed out the windows. A flaming dumpster appeared out of nowhere and careened toward the car. Just as it smashed into the car we looked to our left and saw a phalanx of cops in full riot gear approaching us. They began unloading pepper bombs and other less-lethal ammunition. The crowd fled into the surrounding streets, and the riot was on.

As another anarchist recounted, not everyone immediately understood the significance of these events:

Later that night in the holding cell, some of those arrested had moments of serious regret as they speculated about the possible charges they might face. A seasoned Black organizer who had also been rounded up addressed the group: “In ten years, nah fuck it, in six months you ain’t gonna remember sitting in here right now—all you’ll remember is the night the town stood up.”

Afterwards, according to the report from participants in UA in the Bay, the police, town officials, reformist organizers, and other authoritarians sought to undermine the solidarity that had made the riots possible by focusing blame on white anarchists, casting them as “outside agitators.”1

In the days following the riot, public outrage seemed to focus on anarchists participating in the uprising. News outlets published articles in which they blamed anarchist provocateurs for the “violence.” This was frustrating, but not entirely unexpected. One commentator said, “if they’re blaming us, at least they’re not blaming other [less privileged] participants.” […]

For the record, anarchists were present for all aspects of the uprising, and acted in unity with other rioters, despite others’ subsequent attempts to drive a wedge between anarchists and other participants. There were times when anarchists shared skills garnered through years of street demonstrations, such as how to conceal one’s identity or evade police. But it’s disingenuous to characterize anarchists as playing a leadership role. Anarchists worked side by side with a diverse crowd that night, but the rage that fueled the fire came from those who face brutal police repression every day of their lives.

In *The Failure of Nonviolence, Peter Gelderloos recalls how at a demonstration a week later, aspiring “white allies” from an organization that claimed to oppose white supremacy attempted to exert paternalistic control over both anarchists and angry Black youth in the name of safety:

During the January 14, 2009 protests for Oscar Grant, a week after the first riots, white activists from the Catalyst Project, together with people from different churches and NGOs, donned bright vests and linked arms to protect property and prevent rioting. Many accused any white person they saw (some of whom were Oakland residents, some of whom were not) of irresponsibly endangering youth of color. They didn’t say anything about all the white people who stay home every time the cops kill a young black man.

Despite these challenges, anarchists strengthened their relationships with the grassroots participants in the revolt by playing a significant role in the subsequent legal support process. The issue is discussed in greater detail here. You can read more about the Oscar Grant riots in the text Unfinished Acts.

Anarchists participated in the Oscar Grant riots on account of their rage against police and white supremacy and their desire to deter the state from killing people. But this also reflected intentional strategizing about how anarchists might open up new horizons of possibility:

In December 2008, after the Greek insurrection, a small number of anarchists intentionally promoted two tactical proposals as a way to break out of the impasse that summit-hopping and other approaches from the so-called “anti-globalization era” had reached. These two proposals were university occupations and anti-police revolt. Although both of these had occurred in the United States before, these anarchists believed that they had untapped potential.

These experiments began humbly, with a few dozen people occupying buildings at the New School in New York and a few hundred people rioting in Oakland after Oscar Grant was murdered. The former led indirectly (via the “Occupy Everything” slogan of the student occupation movement and the subsequent occupation of the capitol building in Madison) to the Occupy movement; the latter set a precedent for the revolts in Ferguson and later, in May 2020, Minneapolis. The long-term potential of those models was not immediately apparent in their awkward beginnings, nor were the permutations that the movements arising from those initial examples would undergo.

II. The Riots

Anarchists always seek to participate in struggles against white supremacy, police, and oppression. But in the years following the Oscar Grant Rebellion, many anarchists in the United States shifted from focusing on activist campaigns and mass mobilizations to seeking to participate in and spread social unrest. To some extent, this reflected the influence of overseas anarchist movements and ideas, but it was no coincidence that this occurred after the 2008 recession intensified the pressure on the population at large, especially oppressed communities. Suddenly, although reactionary attitudes lingered (the years 2009-2014 saw a tremendous amount of controversy about “violence” versus “non-violence”), countercultural groups were not the only ones seeking to engage in resistance.

2010-2011

Early in 2010, two participants in Void Network, a Greek anarchist collective, embarked on a speaking tour of the United States to discuss a book about the Greek insurrection of December 2008, We Are an Image from the Future. They presented at the Black Rose infoshop in Portland, Oregon on March 21. The speakers emphasized that when the police kill a person, the essential thing is to act immediately in response with whatever numbers you can muster.

The following day, Portland police murdered Jack Dale Collins, the third killing they had committed in a period of weeks. Local anarchists met in a park and immediately set out, chanting “Cops, pigs, murderers!”—a chant borrowed from the Greek insurrection. When they reached Burnside Avenue, they pulled dumpsters into the street, smashed the windows of a bank and a Starbucks, and clashed with police outside the local police station. A communiqué appeared immediately afterwards reading, in part,

We fight against police violence because we feel rage and sadness whenever they kill someone.

We fight in solidarity with everyone else who fights back. And by fighting, we are remembering what it is like to be human.

In these moments when we surprise ourselves, we catch little glimpses of the world we fight for.

This action introduced property destruction and autonomous black bloc marches in Portland to a context beyond the large demonstrations of the fading anti-war movement. It precipitated a cycle of anti-police struggles in Portland through the spring and summer of 2010, which functioned as a bridge between the Oscar Grant riots and everything that came afterwards. Crucially, anarchists up and down the West Coast were in continuous communication and coordination throughout this period.

On August 30, 2010, a Seattle police officer murdered John T. Williams, a 50-year-old Native American man. Police in the Puget Sound area murdered four other men that same week.

Anarchists in Seattle called for an assembly on September 21, at which to discuss how to respond to police violence. The invitation was open to all, with one caveat:

“Arguments for police reform are not welcome at this assembly. If you choose to express good faith in this violent and oppressive system you will be asked to leave. The only requirement for attendance at this assembly is the desire for the total abolition of the dominant social order that commits violence against us—including the police force. To this end, political parties are unwelcome—including so-called ‘revolutionary’ ones.”

The participants reached a rough consensus that the important thing was to interrupt city officials’ efforts to channel anger into dialogue and reformism. Nonetheless, it was difficult to break the reformist organizers’ grip on what could happen in the streets.

In “Burning the Bridges They Are Building,” one participant describes how months later, in January 2011, a tame protest march organized by the authoritarian Revolutionary Communist Party finally got out of the organizers’ control:

As the march wandered through the crosswalk of a busy intersection, a woman—unknown to the anarchists, unaffiliated with the RCP, and holding only an umbrella—refused to leave the crosswalk. She blocked a city bus, which in turn blocked several lanes of traffic, which quickly backed up for blocks. While she stood there defiantly, she began to mock the other demonstrators for their passivity and cowardice. The few anarchists quickly joined her in the intersection.

To the organizers’ and cops’ dismay, the demonstrators ended up blocking the intersection for hours. This anecdote captures the way that these movements often escalated. The impetus generally came from ordinary people from the communities impacted by police violence; but because of their analysis of power, anarchists were usually among the first to join in.

A series of combative marches took place in Seattle between January and March, in which participants repeatedly damaged police cars and defended each other from police attacks. When it came out that no charges would be filed against the officer who murdered John Williams, many hundreds of people took the streets, taking up the combative tactics that a small number of anarchists had demonstrated. The movement in Seattle showed that the Oscar Grant uprising was not a fluke. As Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin had foreseen, the conditions that made it possible existed all around the United States.

This was born out in the Bay Area the following July, when people responded to a string of police murders by temporarily shutting down multiple Bay Area Rapid Transit stations and once again taking the streets:

Within a few hours of hearing word of SFPD’s latest atrocity, we called for a march against the police in the Mission District. About 100 of us gathered, donned masks, and marched down Valencia St. toward the Mission Police Station. We attacked the first pig car that approached. We attacked ATMs and a Wells Fargo as well. We upturned newspaper boxes and trash bins, throwing them into the streets at the encroaching riot cops. We screamed in the pigs faces and confronted them at their front door. By 1 AM, we had dispersed without arrest.

Anarchists marching in Seattle on February 16, 2011.

At the same time that this sequence of events was playing out in Seattle and San Francisco, movements against police violence were assuming a central role in unrest outside the United States, echoing the events in Greece in 2008. On December 17, 2010, a young Tunisian named Mohamed Bouazizi had set himself on fire to protest his treatment at the hands of police, setting in motion the wave of uprisings that came to be known as the Arab Spring. The day of protest that sparked the Egyptian revolution of 2011 was scheduled for National Police Day, January 25, by the Facebook page We Are All Khaled Said, which memorialized another young man killed by police. In August 2011, riots broke out in the UK in response to the police murder of Mark Duggan.

It isn’t just that the police are called in to repress every movement as soon as it poses any threat to the prevailing distribution of power (although that remains as true as ever). Rather, repression itself has been producing the flashpoints of revolt.

Demonstrators confront police in Egypt at the opening of 2011.

September 2011

On September 17, 2011, the Occupy movement got underway in Manhattan, expressing a protest against the prioritization of finance capital in the state response to the recession but also a rudimentary opposition to capitalism in general. In fact, the movement didn’t gain much traction on the popular imagination until footage of police attacks circulated later that month. After that, Occupy spread like wildfire.

Occupy represented an improvement on the convergence model in that it presented a reproducible and decentralized framework, drawing people to a rapidly proliferating number of flashpoints. The structure of the movement reflected the participation of anarchists from the very beginning—including at least one Greek anarchist, who reputedly was responsible for the intervention that led to the horizontal assemblies.

In Oakland, the legacy of the Oscar Grant riots set the stage for the Bay Area to host the high-water mark of Occupy. When police evicted Occupy Oakland, fracturing the skull of Iraq War veteran Scott Olsen, the movement responded with a general strike including a blockade of the Port of Oakland.

Three years later, in “From Occupy to Ferguson,” we explored how the Occupy movement reached its limits because of pacifism, fundamental contradictions within democracy, and the absence of a critical mass of working-class people of color.

Why did [the Occupy movement] subside without achieving its object of transforming society? First, it offered almost no analysis of racialized power, despite the central role of race in dividing labor struggles and poor people’s resistance in the US. Second, perhaps not coincidentally, its discourse was largely legalistic and reformist—it was premised on the assumption that the laws and institutions of the state are fundamentally beneficial, or at least legitimate. Finally, it began as a political rather than social movement—hence the decision to occupy Wall Street instead of acting on a terrain closer to most people’s everyday lives, as if capitalism were not a ubiquitous relation but something emanating from the stock market. As a result of these three factors, the majority of the participants in Occupy were activists, newly precarious exiles from the middle class, and members of the underclass, in roughly that order; the working poor were notably absent. The simplistic sloganeering of Occupy obscured the lines of conflict that run through our society from top to bottom: “police are part of the 99%” is technically true, economically speaking, but so are most rapists and white supremacists. All of this meant that when the police came to evict the encampments and kill the movement, Occupy had neither the numbers, nor the fierceness, nor the analysis it would have needed to defend itself.

When a movement reaches its limits and subsides, it illustrates the obstacles future movements will have to surpass.

2012-2013

All around the country, however, struggles against police violence were cross-pollinating with the fiercest elements of the Occupy movement. On October 17, 2011, ten days after Occupy Atlanta got underway, a march including anarchists departed from the encampment at Woodruff Park to protest the police murder of 19-year-old Joetavius Stafford. A month later, police murdered Dwight Person in front of his family in an illegal “no-knock” warrant that was addressed to a different house, and another march departed from the park. Shortly before Christmas, a police officer shot 19-year-old Ariston Waiters in the back while he was handcuffed, and once again, a march took place in response. Each of these involved a larger contingent of anarchists employing black bloc tactics, as chronicled in “Don’t Die Wondering: Atlanta Against the Police Winter 2011–2012.”

On February 26, 2012, a white vigilante murdered Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old Black young man in Florida, enraging people all around the country. In Atlanta, institutional organizers sought to gain control of a response scheduled for March 29:

A friend of ours had made an anonymous Facebook profile to create the event and had billed it as a march. This was all very intentional. A few careerists, however, used the opportunity to get a permit for the event and to move it to the Capitol. They held press conferences announcing that it was happening there and that it would simply be a rally, not a march. They, of course, get to decide who speaks and who doesn’t.

Nonetheless, after a carefully controlled rally, a multiethnic crowd of several dozen people set off on a breakaway march.

Someone jogged up to a ParkAtlanta meter and smashed the screen with a large wooden dowel bearing a black flag. Someone else, without a shirt tied around their face, kicked a newspaper stand into the street, and several others dragged them into the intersection. A capitol cop jogged up from behind the march and began chastising us: “Hey you! Pick that box up this minute!” People yelled back at him and picked up the pace a little bit. The march turned a corner and found itself on an empty street with a large number of police cruisers parked outside a government building. The lone cop following the march quickly turned and ran when someone jogged up to the nearest squad car and smashed out its front window with a wooden dowel.

“Ohhhhh!!!!” the crowd all yelled at once. Someone else ran up behind them with a hammer. They took out the windows of another squad car, and someone after them jumped up onto the car and stomped in the windshield.

While some people dragged barricades into the streets, others continued smashing the windows out of every police vehicle and luxury car on the street for two blocks.

In July 2012, locals in Anaheim, California rioted after officers murdered a man. In March 2013, people in Brooklyn, New York responded to police murdering 16-year-old Kimani Gray by marching on the 67th Precinct and pelting it with garbage and bottles. In Durham, North Carolina, in November 2013, when 17-year-old Jesus “Chuy” Huerta mysteriously died of a gunshot wound to his head with his hands cuffed behind his back in the back of a police cruiser, anarchists worked with his family to organize a demonstration during which protesters marched to the police station and smashed out its windows.

Each of these outbreaks of rebellion lasted only a few hours at a time. But understood as a series, they show that people around the United States were experimenting with more confrontational forms of resistance, learning from each other in a dialogue comprised of actions as well as words. In many cases, anarchists were among the only explicitly politicized participants.

From the beginning, police, politicians, liberals, authoritarian socialists, and other aspiring leaders had sought to marginalize anarchists by depicting them as white thrill seekers, promoting a narrative according to which it was anarchists, not police, who were endangering people of color. As people experimented together in the streets, they also began to push back against this way of weaponizing identity discourse to suppress resistance. In April 2012, participants in the movements in Oakland had published “Who Is Oakland?”—a lucid corrective:

Anti-oppression, civil rights, and decolonization struggles clearly reveal that if resistance is even slightly effective, the people who struggle are in danger. The choice is not between danger and safety, but between the uncertain dangers of revolt and the certainty of continued violence, deprivation, and death. […]

No demographic category of people could possibly share an identical set of political beliefs, cultural identities, or personal values. Accounts of racial, gender, and sexual oppression as “intersectional” continue to treat identity categories as coherent communities with shared values and ways of knowing the world. No individual or organization can speak for people of color, women, the world’s colonized populations, workers, or any demographic category as a whole—although activists of color, female and queer activists, and labor activists from the Global North routinely and arrogantly claim this right. These “representatives” and institutions speak on behalf of social categories which are not, in fact, communities of shared opinion.

In May 2014, Indigenous Action published “Accomplices Not Allies,” a critique of “allies” who continue to center themselves even as they pretend to put themselves at the disposal of others’ struggles for liberation:

Where struggle is commodity, allyship is currency. Ally has also become an identity, disembodied from any real mutual understanding of support. […]

This kind of relationship generally fosters exploitation between both the oppressed and oppressor. The ally and the allied-with become entangled in an abusive relationship.

They argued that those who are fighting for their own liberation need comrades who have their own reasons to fight:

We need to know who has our backs, or more appropriately: who is with us, at our sides?

These texts helped to legitimize the idea that the way to act in solidarity with those on the receiving end of police violence was to fight alongside them, not to try to deescalate struggles.

Demonstrators in Ferguson flip a police car in November 2014.

Elsewhere around the globe, resistance to police violence continued to set off upheavals. In 2013, the fare hike protests in Brazil and the Gezi Resistance in Turkey both metastasized from small single-issue protests to massive uprisings as a result of police repression. The same thing happened in Eastern Europe, setting off the Ukrainian revolution at the end of 2013 and sparking the Bosnian uprising of February 2014.

In fact, the window of possibility that had opened with the insurrection in Greece was already closing as authoritarian regimes and politics reasserted themselves around the world. Nonetheless, in the United States, resistance to the police was only just getting underway.

Militarized police in Ferguson, August 2014.

III. The Ferguson Uprising

On July 13, 2013, after the acquittal of the man who murdered Trayvon Martin, people around the country had gathered in protest. At the demonstration in St. Louis on July 14, anarchists encountered other protesters that they were to meet again a year later. This shows how the movement against police was already starting to produce waves of countrywide action while bringing together people who were prepared to push things further.

August 2014

On August 9, 2014, a police officer stopped an 18-year-old Black man named Michael Brown. Witnesses report that the officer shot Brown as he fled with his hands up in surrender. A crowd quickly assembled from the neighborhood; some locals fired shots into the air and set a dumpster alight. Police responded with an armored riot vehicle, a helicopter, dogs, and assault rifles—but furious mourners forced them to withdraw.

The next day, people gathered for a prayer vigil at the site of the shooting, including anarchists from St. Louis. The crowd marched to the police line, yelling insults and throwing things. Police attempted to drive through the crowd, but people surrounded them and smashed out their windows. The police fled.

One anarchist described the ensuing situation:

The block is ours. The police are maintaining lines at Ferguson Avenue (to the south) and just north of the bridge for the 270 interchange (to the north). The mile or so between is totally unpoliced and filled with thousands of people.

This commercial stretch, full of parasitical businesses, has numerous small roads leading east into the densely populated neighborhoods just a block away. The police, too afraid and outnumbered to enter a residential area seething with outrage, are unable to block those streets. As they hear about what is going on, people are pouring into the commercial district on foot, in cars, on motorcycles. For once, the geography of this suburb is on our side.

The uprising in Ferguson crossed a crucial threshold because, for the first time, the rebellion continued beyond a single day. As the unrest persisted, it offered a point of convergence for all who wanted to resist police violence. For nearly two weeks, demonstrators faced off with militarized police every night as people around the country watched the events unfolding via news and social media and debated the issues of police violence, repression, and militant tactics.

Afterwards, comparing the uprising in Ferguson to the Occupy movement, we argued that the uprising had overcome the limits that the Occupy movement had reached:

It’s possible to understand the social momentum originating in Ferguson as an answer to the failures of Occupy. Where Occupy whitewashed the issue of race, the protests in Ferguson placed it front and center. Where Occupy confined itself to the unfavorable terrain of “political” physical sites and reformist demands, the people who rose up in Ferguson were fighting on their own streets for their own very lives. Whereas, with the temporary exception of Occupy Oakland, Occupy lacked the will to stand down the police, people in Ferguson braved tear gas and even bullets to do just that. Where Occupy sought to conceal all the different forms of hierarchy and strife that cut through this society beneath the unifying banner of “the 99%,” the conflicts in Ferguson compelled everyone to confront them. […]

The momentum proceeding from the demonstrations in Ferguson has its own internal tensions, which will become more apparent the further it goes. Is the problem police brutality, or policing itself? Is the rightful protagonist of this struggle the local poor person of color, the respectable leader of color, the white ally, or everyone who opposes police killings? If it is the latter, how should we deal with the power imbalances within this “everyone”? How should demonstrators from outside the most targeted communities relate to conflicts playing out within them, such as disputes over tactics or risk?

You can read a full timeline of the Ferguson uprising here and a day-by-day account of one anarchist’s participation here.

A demonstrator in Ferguson faces off with a line of riot police in 2014.

November-December 2014

Over the following three months, people around the country reflected on the example of the brave fighters who confronted the police in Ferguson—and all the while, police continued to murder people in St. Louis and everywhere else, stoking rage and urgency. On November 24, when the legal system failed to indict the officer who murdered Michael Brown, demonstrators once again took the streets of Ferguson, confronting a well-prepared, fully militarized occupying army of police and National Guard and nonetheless striking powerful blows against them.

This set off solidarity demonstrations all around the country, after the fashion of the viral model demonstrated by the Occupy movement. The clashes of November and December 2014 arguably reached the highest pitch that popular struggle had attained in the United States in years. The Bay Area saw seventeen consecutive days of marches, vandalism, looting, and freeway blockades.

2015-2016

On April 12, 2015, police in Baltimore arrested and intentionally brutalized Freddie Gray. He died of his injuries one week later. A week after that, demonstrators gathered for a protest that immediately spiraled out of control. Within two days, riots, looting, and fires were breaking out all over the city, including in some of the wealthier neighborhoods. The mayor declared a state of emergency, called in police from around the state along with the National Guard, and announced a seven-day curfew.

The revolt in Baltimore had escalated more rapidly than the uprising in Ferguson, but the authorities had brought in the National Guard more quickly, as well, shutting the window of possibility.

Less than two months later, on June 17, 2015, Dylann Roof carried out a white supremacist mass murder at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Having been outflanked by grassroots resistance in the streets, the forces of white supremacy were falling back on non-state terrorism.

In August 2015, reflecting on the sequence of events across the preceding year, we recognized that future uprisings would have to occur everywhere at once in order to outflank the repression mobilized against them. At the same time, we discerned that a white supremacist backlash was on the way and noted the ways that the revolts were still limited by a narrative prioritizing identity as a measure of the legitimacy of resistance. The conclusion of the essay is worth quoting in full.

It is dangerous and unethical to leave the greatest risks to the most vulnerable people. If it makes sense for the most marginalized and targeted to risk their lives to interrupt the functioning of the system that is killing them, it makes even more sense for the rest of us to do so. It’s not a question of understanding the uprisings, but of joining and extending them in order to render them unnecessary. That doesn’t necessarily mean invading others’ neighborhoods: the next time a Ferguson or a West Baltimore erupts, it might be most effective for those who wish to show solidarity to initiate actions elsewhere, in order to overextend the authorities. Nor should it mean centralizing ourselves in the narrative: solidarity means taking on the same risks that others are exposed to—nothing more, nothing less.

The precarious rapport de force that has lasted since the Baltimore uprising will likely persist until another demographic enters the conflict. It’s not clear how much further the state can go to maintain the current order by means of pure force. If uprisings occurred in multiple cities in the same region at the same time, or if a much broader range of people got involved, all bets would be off.

But as intimated above, the next demographic to enter the space of conflict might well be a reactionary force. South Carolina is not the only place in which struggles against state violence have shifted seamlessly into struggles against autonomous white supremacists. Some anarchists and fellow travelers have glibly invoked “social war” or “civil war,” without fully grasping that such wars usually end up playing out along ethnic and religious lines in the most reactionary manner. As the tensions in our society increase, it is up to us to render it possible to imagine other lines of conflict. The Dylann Roofs of the world and their equivalents within the halls of power want nothing better than to see society split into warring racial factions, with poor whites joining police and other defenders of the middle class to suppress the rage of the black and disaffected. White people must not countenance this division, even out of a wrongheaded desire to stand aside out of respect for black autonomy. That would spell doom for the most marginalized people in this struggle, however much good liberals might applaud their courageous efforts from afar. Rather, we have to produce a narrative of multiethnic struggle against white supremacy and capitalism by participating directly in the clashes that are occurring right now—both so that it will be impossible for white supremacists to convince potential converts that the important lines dividing society are racial, and so that those who are more racially and economically marginalized than us will not have cause to conclude that they have indeed been abandoned.

Fighting white supremacy in this context means spreading the clashes with the authorities, while crushing autonomous racist initiatives wherever they appear. It means confronting fascists—an essentially rearguard battle—but it also means taking the initiative in attacking capitalism and the state, intensifying the struggles we are already in. Only by foregrounding anarchist solutions to the problems of poor people, including poor white people, can we make it impossible for racists to recruit from the ranks of the poor, white, and angry.

A demonstrator in Ferguson displays a sign reading “Nice night for a revolution” in 2014.

Police continued to murder people, and revolts continued to break out in response, but as a consequence of the authorities’ readiness to respond immediately with heavy-handed repression, the movement had reached a plateau.

On November 15, 2015, police officers in Minneapolis murdered Jamar Clark, a 24-year-old Black man. In response, demonstrators established an occupation outside the fourth police precinct. On November 23, far-right vigilantes attacked them, shooting five people. Nonetheless, the following July, when a police officer murdered Philando Castile in front of his partner and child during a traffic stop, demonstrators took the streets again, blocking freeway traffic and defending themselves from police.

That same July, Baton Rouge police officers murdered Alton Sterling, sparking protests in Baton Rouge and Dallas; during the latter, a gunman killed five police officers before the police killed him with a robot-delivered bomb. On August 13, 2016, the fatal police shooting of 23-year-old Sylville Smith triggered a riot in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The next month, there were riots in Charlotte, North Carolina in response to the police murdering Keith Lamont Scott.

By this point, anarchists were still participating in the front lines of these protests, but in some ways, they had lost ground within the movement. In response to the explosion of activity following the Ferguson uprising, formal Black Lives Matter groups had achieved a new hegemony within protest organizing. Whereas previously, institutional leadership had sought to prevent demonstrators from engaging in unpermitted marches or blocking freeways—with the consequence that when that failed, spaces of freedom opened up—now a new generation of leaders and protest marshals was prepared to lead marches, even onto freeways, but still sought to sideline anarchists in order to retain control. As the tide went out and mass participation dropped, the participants that remained were largely activist groups that successfully leveraged the usual charges of “privilege” and “outside agitators” to marginalize anarchists.

Many anarchists shifted focus from fighting the police in anti-racist struggles to fighting the fascist movements that were on the rise. This was a risky proposition: it was not auspicious to cede the ground of anti-police discourse while moving to an even more potentially lethal field of conflict. But with fascist violence spreading around the country, many anarchists concluded that they had no choice.

A CrimethInc. sticker reading “Police Not Welcome” behind the burned-out husk of the Third Precinct in Minneapolis in 2020.

IV. The Trump Years

When Donald Trump came into power in 2017, anarchists around the country swung into action, marching against his inauguration, helping to shut down airports in response to the Muslim Ban, and defending their communities from fascist mobilizations.

Yet mysteriously, revolts in response to police murders suddenly ceased. This is a historical enigma yet to be properly accounted for. Police did not by any means stop murdering Black and brown people. As we wrote in our retrospective on the year 2017,

The only city to see a major movement against racist policing in 2017 was St. Louis, where the social movements and tensions that gave rise to the uprising of 2014 had continued unabated. This points to some of the ways that the reaction represented by the Trump administration succeeded in setting back social movements and taking possibilities off the table. Have we missed opportunities to let the communities that are most directly targeted by police know that we are still ready to stand with them when they stand up for themselves outside the useless channels of reformist organizing?

Perhaps all that changed was that anarchists and other activists were so busy reacting to fascist violence that they failed to provide the necessary solidarity to the communities most targeted by police violence. The pause in anti-police uprisings seems to bear out the hypothesis that, despite the fact that anarchists were rarely central to the revolts, there was some sort of subterranean connection between the two—if only in that they were both downstream of the same developments.

The pause in uprisings continued until May 2020. There were a few protests when police killed people, but nothing like what had occurred in Oakland, Seattle, Ferguson, Baltimore, Minneapolis, or Charlotte. This seems to suggest that for good or ill, these uprisings were not just occurring as a consequence of localized outrage on the part of targeted communities, but also because of a shared discourse and imagination regarding the possibility of revolt and the form it could take. The solidarity and support of many different communities and groups, including anarchists, played a crucial role.

So revolts against police aren’t just mechanistically produced by police violence. They depend on a shared vision, shared reference points, familiarity with previous precedents, a collective capacity to mourn and to care for each other, a shared sentiment that the police lack legitimacy, disillusionment with reform measures, and networks and community institutions that have not been integrated into the processes that preserve the ruling order.

Graffiti in New York City during the hot summer of 2020.

In 2020, the pandemic hit the United States, upending everything. As we argued at the time, this came on the heels of the successive failures of various legal, judicial, and electoral challenges to the order Trump presided over:

By the time the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States in full force, all the statist means of seeking social change had been exhausted. Trump exacerbated the situation, seizing the opportunity to arrange a massive wealth transfer of billions of dollars to the richest stratum of society in the midst of the worst economic recession in living memory. In this context, millions of people in the US, alongside billions around the world, spent mid-March to late May in isolation, contemplating their own mortality. It had never been clearer that the institutions of power are fundamentally hostile and destructive to the lives of ordinary people.

This is why, when the news of Black rebels’ response to George Floyd’s murder spread, even white middle-class liberals felt the tragedy viscerally. The pandemic suspended some of the mechanisms that ordinarily insulate the privileged from identifying with the most marginalized.

Those who are always targeted by police, who suffer most from racism and poverty, recognized that it was now or never. Heroically, all around the US, they staked their lives in an all-out attack on their oppressors—and millions of stir-crazy people of all classes and backgrounds joined them in the streets.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

One additional point bears adding: owing to right-wing opposition to the COVID-19 lockdown, the far right was more opposed to police in May 2020 than it had previously been in living memory. That internal confusion bought the revolt a couple weeks at the beginning of June 2020 during which Trump’s supporters were not able to mobilize an effective reaction. Finally, in mid-June, Tucker Carlson was able to catalyze right-wing opposition with his trademark hostile and mendacious coverage of the police-free zone in Seattle.

“The uprising in Minneapolis brings all the unsettled debts of that era back into play, but in a totally different context, in which a lot more people have been radicalized, society is much more polarized, and it is increasingly clear to everyone that—whether from the bullets of the police, COVID-19, or global climate change—our lives are at stake.”

Los Angeles during the 2020 uprising.

It remains for a future analysis to trace in detail how the Biden administration systematically undermined the progress that the movement against police had achieved, paving the way for its own defeat at the hands of a resurgent fascist movement under Trump, and how anarchists sought to prepare for this by continuing the anti-police movement in the form of the fight to stop Cop City.

Retracing the trajectory that led from the Rodney King riots to the George Floyd Rebellion, we can see both the potential and the limitations of the role that anarchists have played. Although anarchists usually comprised only a small part of the movement, they were one of the only ideologically driven groups that consistently showed up from the very beginning all the way through to the end. Again and again, the movement grew exponentially thanks to the moments when it exploded out of control as a consequence of ungovernable, confrontational action; it is significant that anarchists were one of the only groups consistently supporting this approach from the beginning.

At the same time, from the beginning to the present, the movement against police has repeatedly reached limits the same way that the “anti-globalization” movement and the Occupy movement did. This is not just a consequence of repression. It is also due to counter-insurgency tactics from both within and without, and from the fact that although anarchists have often succeeded at introducing new tactics and discourse into movements, they have often become disoriented when they are no longer the ones determining the pace of escalation.

It remains an open question how the next phase of the movement can unfold under an increasingly repressive and technologically advanced government. But the question has never been more important.

Further Reading

You can read accounts of some of the events described here in the collection We Fight: Three Decades of Rebellion Against the Police .

- A Beginner’s Guide to Targeted Property Destruction

- Big Brick Energy: A multi-city study of the 2020 George Floyd uprising

- In Defense of Rioting

- In Defense of Looting

- In Defense of the Ferguson Riots

- The Illegitimacy of Violence, the Violence of Legitimacy

- Police: An Ethnography

- The Thin Blue Line Is a Burning Fuse

- What They Mean When They Say Peace

- What Will It Take to Stop the Police from Killing?

- Why Break Windows?

-

As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Never again can we afford to live with the narrow, provincial ‘outside agitator’ idea. Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.” ↩